US-Iran tensions: a gamechanger for the global economy?

Recent events in the Middle East have provided a reminder that the region still has the capacity to unsettle financial markets. In the wake of the US assassination of Qassem Soleimani on 3 January, the oil price jumped nearly 5% and global equity markets wobbled. However, the subsequent de-escalation of US-Iran tensions saw oil prices fall back and global equity markets go on to hit record highs.

The key question for investors going forward is whether instability in the region will prove a gamechanger regarding the outlook for the global economy and financial markets. Several factors suggest that, for 2020 at least, this will probably not be the case.

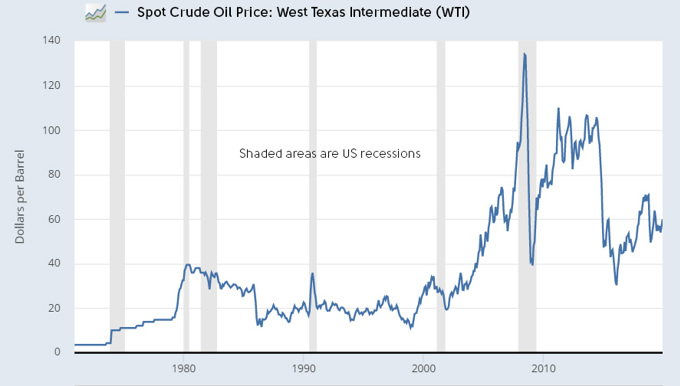

Historically, the primary channel through which tensions in the Middle East have impacted the global economy and financial markets has been the oil price. Spikes in the oil price have preceded recessions in the past, most notably during the first OPEC oil price shock of 1973.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The rise in the oil price at the start of the year was fleeting because feared disruptions to oil supplies failed to materialise. However, given the possibility of further attacks, there is still a considerable risk that oil prices could see a more lasting increase during the coming months.

The risk to oil supplies

The big fear in markets would be if Iran followed through on threats to close the Strait of Hormuz. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) describes the strait as the world's most important oil “chokepoint”; some 21 million barrels per day (bpd), or about 21% of global consumption, flow through it. Closure of the strait would result in disruption that would dwarf previous supply outages. By way of comparison, the attacks on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq and Khurais oil processing facilities in September 2019 cut production by around six million bpd. Oil analysts anticipate that an attempt by Iran to close the Strait of Hormuz could send the oil price above US$100 per barrel.

Such a turn of events, while possible, looks unlikely. Analysts in the region note that there is great pressure from Iran’s regional allies and its trading partners not to pursue such a course of action. In particular, China, which buys around half of Iran’s oil exports and is heavily dependent on supplies transported via the strait, is likely to use its considerable influence to prevent such an outcome. In addition, an attempt to close the strait could provoke a severe US military response, which would be costly to Iran and could mean that any disruption is short-lived.

Although the ongoing instability in the Middle East holds out the prospect of periodic spikes in the oil price, several factors argue against a steep, sustained increase. The growth of US shale oil – production of which can be turned on and off more quickly than conventional drilling – has arguably acted to dampen price volatility. The boom in the shale industry has seen US oil production rise to nearly 13 million bpd at the end of last year from around 5.5 million bpd ten years earlier. With shale production more responsive to changes in price, the expectation is that a jump in the price of oil would swiftly bring forth increased investment and output, which would in turn cause prices to fall back.

Admittedly, difficult financing conditions for some companies within the shale industry might limit the degree to which US output could respond. However, it is also the case that, having cut output to support prices last year, the so-called OPEC+ group of oil producing countries currently have spare capacity to increase production in the event of a supply squeeze. The EIA also expects higher output this year from the likes of Brazil, Norway and Canada.

A less oil-intensive global economy

While supply dynamics have made a sustained rise in the oil price less likely, the global economy has also become less vulnerable to an increase in the cost of fuel. Developed economies are now generally less dependent on oil than they were, as fuel efficiency has improved, the use of renewables has increased, and the service sector has grown in importance.

In developed market economies today, a unit of real GDP requires less than 40% of the oil required to create a unit of GDP in 1970. Growth in emerging market economies tends to be more energy intensive than in developed ones, but even here, the relative importance of oil has fallen back during the last 20 years or so.

Of course, a rising oil price creates winners (oil producers) and losers (oil consumers). US consumers have been particularly vulnerable because, as gasoline is taxed lightly, the price paid at the pump is more sensitive to swings in the wholesale price of oil. (US consumers pay about 56 cents in tax per gallon of petrol – around a quarter of the OECD* average). As oil and gasoline prices go up, households have less money to spend on other goods and services. In addition, rising fuel bills squeeze the profits of companies where energy is a significant input cost. However, as the shale oil industry has grown and the US has become a net oil exporter, these potential headwinds to GDP growth have been offset somewhat by the prospect of increased investment in the energy sector which can be expected to follow a rise in the oil price.

Moreover, oil exporting countries are now more likely to spend increased revenues resulting from a rise in the oil price. With public finances under strain in several oil producing economies, additional revenues are less likely to be saved (as tended to be the case in the 1970s) thereby dampening the negative impact on global demand from a rise in the oil price.

*Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The central bank response

A key consideration regarding the impact of an oil price spike on the global economy and financial markets is how central banks would react. In developed economies, the backdrop of stable inflation expectations, flexible labour markets and competitive product markets suggests an oil-induced wage-price inflation spiral is unlikely. Inflation is generally below central banks’ targets and, these days, policymakers tend to ‘look through’ changes in the price level that are deemed to be transitory.

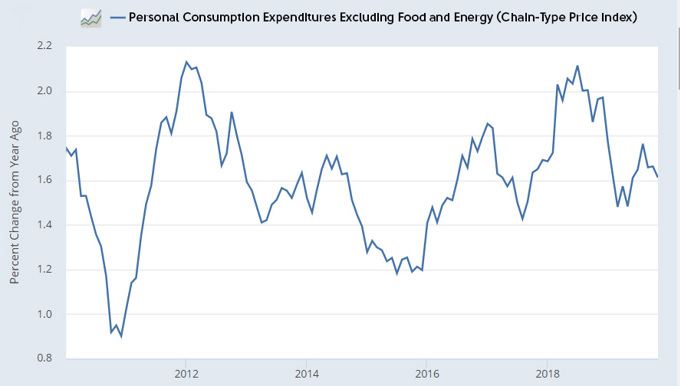

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

As a result of low taxes on gasoline, the upside risks to headline inflation from a rise in the oil price are probably greatest in the US. However, the US central bank, the Federal Reserve (Fed), tends to focus on a core gauge of inflation - the so-called core PCE deflator - which excludes food and energy prices. Indeed, inflation on this measure has spent most of the last 10 years below the Fed’s 2% target, and indications are that the Fed is considering a new policy framework under which it would foster a period of above-target inflation to compensate for earlier undershoots (see our December 2019 commentary). This suggests that the Fed will not be in a hurry to hike rates even if ‘second-round’ effects following an upward move in the oil price caused core inflation to move above 2%.

Indeed, with the global economy still fragile and manufacturers still struggling, it would not be surprising if the Fed and other developed market central banks were more concerned about the potential downside growth risks from an oil price spike than the upside inflation risks. Under such circumstances, therefore, real (i.e. after adjusting for inflation) interest rates are more likely to fall than rise in the event of an escalation in hostilities in the Middle East.

A gamechanger?

As with any geopolitical risk, the extent to which tensions in the Middle East have a durable impact on global markets depends on the degree to which underlying fundamentals are impacted. At the current juncture, global equity markets are pushing higher on the back of supportive monetary policy (low real interest rates and expanding central bank balance sheets) and gradually improving growth prospects following the global slowdown of 2018-19. There is a clear risk of renewed hostilities that could result in damage to oil infrastructure in the region. And the threat of Iranian-sponsored cyberattacks adds a new dimension to the conflict. However, President Trump will be wary that renewed tensions could damage his re-election prospects, not least as higher oil prices would hurt most voters’ finances. While developments in the Middle East will remain a potential source of short-term volatility, it seems unlikely they will change a macro narrative that should be broadly supportive of global equity markets this year.

This article is for generic information only and is not suggesting a suitable investment strategy for you. You should seek independent financial advice that takes your individual circumstances into account prior to proceeding with any course of action.